If you’re just born in the wrong country, or social class, you may have a 60% less chance of surviving cancer. On World Cancer Day, experts call to fight “inequities”: not a matter of chance, but of modifiable factors which might save millions of lives.

Calin lives in the Romanian city of Cluj. He suffers from melanoma and his mother died from colorectal cancer, aged 58. “It took two months just for a colonoscopy,” he recalls. “Halfway through the chemotherapy, she had to move to another region, because the one she had been treated in lacked appropriate medicine. An earlier diagnosis would have definitively saved her life.” Things have evolved since, but almost 20 years later, Romanian cancer patients still voice similar complaints. “I have experienced the same in my family,” says Camelia. Herself treated for breast cancer, and she says that several of her relatives have been diagnosed too late. “Lots of services lack basic medication and equipment, we don’t have proper guidelines, and general practitioners don’t know what protocols to apply. For patients, it can be a real nightmare,” says Adrian Udrea, oncologist and medical director of a private cancer clinic in Cluj. Such dysfunctions contribute to Romania’s poor performance in tackling cancer: historically the second cause of death nationwide, it kills here more than in any other EU country.

“If you’re a child and you develop cancer in a low- or middle-income country your chances of survival are 20%, whilst in North America and most of Europe they are over 80%, simply because medicine and diagnostics are available,” says Cary Adams, CEO of the Union of International Cancer Control, which organizes, every 4 February, the World Cancer Day. This year marks the second of a 3-year campaign aimed at reducing the so-called “inequities”: differences in health care and health outcomes that are not predetermined and can be therefore modified. “This year alone cancer was responsible for 10 million deaths worldwide. Over 70% of them occurred in countries where individuals don’t have access to proper treatment and care.” A scientist at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Salvatore Vaccarella is co-author of a recent report on “socioeconomic inequalities” in Europe. “There is a clear geographical divide,” he says. “In Eastern and Baltic countries 50% of cancers in men are associated with such inequalities; and despite a lower incidence, the mortality rate is higher than in the rest of the continent.”

“The biggest difference with Western Europe is the access to diagnosis and treatments, respectful of the oncology standards,” says Udrea. “In Romania, we are still years away on procedures and policies. There are no guidelines for the patients, and this can translate into a deadly waste of time.” IARC’s report also reveals that if for highly educated women, no matter where they live, the risk of dying from cervical cancer is, for instance, relatively low; for less affluent and educated ones there is a huge geographic gap. “In Western Europe, it is in principle fully preventable whilst, in Eastern and Baltic countries, the risk level almost equals that of Sub-Saharan Africa.” This is one of the devastating effects of what experts call “social gradient”: “It is a fact that cancer doesn’t impact the entire population equally. The lower the socioeconomic position, the higher the risk”, explains Vaccarella. “If in Washington you move 15 blocks away from the White House, you end up in a predominantly black community, where women have a lower survival rate from breast cancer than many parts of Africa,” adds Adams.

Such differences within the same country or city mainly depend on the greater exposure to cancer risks in populations with low education and socioeconomic status. “Poorer communities are less informed and less aware. They tend to smoke and drink more, and live less healthy lives. They are also unaware of the signs and symptoms of cancer and so they often turn to the health system too late,” he explains. Disadvantaged populations also have “limited access to preventive measures, early diagnosis, and effective treatments because of barriers such as low health literacy, difficulty to navigate the health system, and limited financial and material possibilities,” says Vaccarella. Inequalities within the same country may also depend on the degree of regional autonomy. “In Spain, the health system is not centralized, but largely delegated to its 17 autonomous communities. Some of them are more developed in diagnostic procedures or treatments, and others in specific clinical trials, so such disparities may cause patients significant problems,” says José Antonio López-Guerrero, Head of the molecular biology laboratory at IVO, the Valencian Oncology Institute.

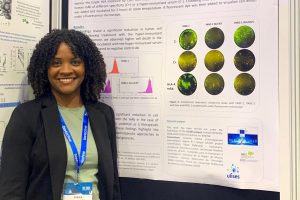

Within the European project Ulises, López-Guerrero is working on a new nanotechnology-based treatment, aimed at fighting pancreatic cancer. “It’s one of the deadliest,” he says. “It presents 3-year mortality rates of around 90% and this is also why we focused on it. We use the nanoparticles as a Trojan Horse. They deliver a DNA, aimed at making tumor cells visible by the immune system, and transform the tumour into something which will be rejected by the patient’s body as it can happen during transplants.” As the final goal is to produce an immune response similar to a “vaccine effect”, the impact could be enormous. “If it proves to be effective, not only pancreatic cancer would be basically eradicated, but the same approach could be adopted with other cancers.” Even though the results of the vitro tests are encouraging, it will still take years before this new therapy is available for use. In the meantime, says Guerrero, “access to clinical trials is one of the main alternatives for patients, but not all of them can cross the country to get what they need.”

Experts agree in considering “cancer control plans” as key tools to identify and address inequities within each country. “We have noted that if you have them in place, and they are supported by good data and information, they can prove very effective,” says Adams. A few months after Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan was released, in February 2021, Romania launched in turn its new national plan. “On paper, it could be a game-changer, but I remain sceptical. We now have more equipment and more money from the European Union, but the people charged of implementing it are the same who failed to make things evolve in the past 35 years,” says Udrea. However, the wind of change blowing across Europe allows Vaccarella some optimism: “People researching these topics have long been taken for fools. Now everybody is realizing that we are not and that millions of lives are at stake.” Things are not going to change overnight, he says. But it is crucial that from now on, any study and intervention to tackle cancer takes into account the existing inequities. “We need more governments to address them, and we need more heads of state taking position,” acknowledges Adams. “Cancer is a long-term game, and our campaign is just a starting point.”

(Article written by Diego Giuliani)