Laura has beaten cancer but never been the same since. After being refused loans, mortgages, and adoption, she understood being one of many cancer survivors facing discrimination. And made of it a political commitment to their rights. Because “we are not half people, and still have all our dignity intact. And this is what I’m fighting for”

Cancer is not a death sentence, anymore.

The latest scientific research and data account for over 20 million cancer survivors in Europe, but prejudices against them die hard and are at the roots of multiple discrimination. Experts and patient organizations are unanimous: even after they’ve regained their health, individuals attempting to return to their ‘normal lives’ quickly realize they face obstacles in getting access to financial services for buying property, adopting a child, or advancing in their careers.

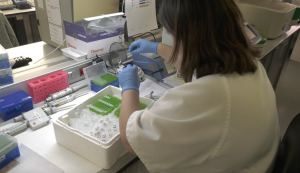

According to some estimates, in 10 to 20 years, one out of three women and two out of the men will have cancer, but survival rates will grow too. Much hope is pinned on innovative therapies, like a “nanotechnology-based” treatment aimed at producing an immune response similar to a “vaccine effect”, which is now under development within the European project Ulises.

Such pioneering therapies take a long time before becoming accessible to patients, but in the long run, their effects are immense. The number of cancer survivors increases by 3% every year and, for instance, over 95% of men diagnosed with testis cancer between the ages of 20 and 30 can now be cured. “It is first and foremost the equation cancer equal to death sentence that we must revolutionize. Science is doing it through research, but it is up to us to change the social perception”, says Laura Marziali. Herself a survivor, she was diagnosed with cancer at the age of 28 and has since devoted her “second life” to advocating for the rights of patients and fighting the discrimination against them.

You speak of your cancer as a turning point, between a first and second “half-time” in your life. Why?

The discovery of cancer made me realize that until then, I had wasted time that could have been filled with everything I loved. The diagnosis came at a stage in life where you would never think you could be affected by such an illness. Yet, it indeed touched me a lot. It turned my life upside down. It touched my body, my deepest identity. I started questioning myself about the meaning of life, about death, about what it means to have a changing body that would soon undergo major therapies and go through early menopause. And all this in a society that does not accept fragility, but constantly judges it.

What kind of judgements?

The day after my discharge from the hospital, I already noticed that I was perceived as different. One of the first signs came from a theater director who considered me too weakened to resume my role, but I didn’t give much importance to it. Then, little by little, I went back to a more or less ‘ordinary life’, but due to both my early menopause and the therapies that I was undergoing, I was fluctuating very quickly between gaining and losing a lot of weight. People around me kept telling me to go on a diet or to eat more. Not only did my new body become a ‘mausoleum of unsolicited judgments’, but men also started turning their backs on me because I could not give them the children they wanted. On an emotional, sexual, and relational level, the impact was therefore immediately enormous.

And this is when you realized being discriminated…

Not yet, actually. Not being able to have children, I had also started to enquire about the adoption process, but the social worker I approached was adamant: ‘You’re not even married,’ she told me. ‘Let alone if, with the cancer you had, you get a child!’ Then I had to buy a new car, but when it came to negotiating the terms of the loan, the insurance company that was supposed to secure it told me: ‘We can’t take on this responsibility, you had a tumor that could return at any moment. However, due to the illness, I had worked very little and so at first I thought it depended on my fragile financial situation. What opened my eyes was a collection of signatures by the Aiom Foundation against discrimination against cancer patients. It was then that I realized I was not an isolated case and that I had to do something to prevent others from having the same experience as me.

What did you do, then?

Facing the various stages of the illness led me to embrace a political perspective: it made me reflect on the impact of cancer on a social and collective level. From that moment on, my goal becomes to let the world know that we can and must react to these discriminations. I start talking about it on social media, and immediately I begin receiving dozens, hundreds of testimonies: people who were refused mortgages and loans, who couldn’t adopt, but also who lost their jobs or were excluded from competitions in the police force. I realize then that my theatre experience can be a tool to share my experience. For the first time in my life, I had a clear goal, which resulted in the combination of activism and artistic research.

This combination gave birth to both a voluntary association and an improvisional theatre show of the same name, “C’è tempo” (“There is still time”)

In the first part, I share my experience, while in the second one, there’s a debate with a panel of professionals: we talk about prevention, care for marginalized people, and more broadly about this “second phase” of life that begins after a cancer diagnosis. This year, we did only five stages, but I’m still exhausted because recounting my story is always emotionally draining.

Your voluntary association has been very active in favour of a law, which has just been passed by the Italian Parliament on the ‘Right to be forgotten’: the right of cancer survivors not to be discriminated against in light of their medical history. Will this be enough or will action have to be taken on other fronts as well?

For the moment, this law will serve to curb a long-standing trend of discrimination. It’s a starting point, but to strengthen other protections or establish additional ones. Crucial in the first place will be information because, like me initially, many are unaware of being victims. We have to inform patients, survivors, but also paramedical staff, doctors who are unaware of the ‘Right to be forgotten’, and institutions and citizens in general, as well.

It sound like you are calling for a change of mindset..

What corners us is the death sentence that is still associated with cancer, but today cancer can be cured. It is first and foremost this paradigm that we must revolutionise. Science is doing it through research, but it is up to us to change the social perception. Even if cancer is behind us, we cancer survivors are still perceived as broken and vulnerable, as people who have nothing more to offer to our society. But no, we are not half people, we’re whole individuals with all our dignity intact. And it is this dignity that I’m fighting for.

Interview made by Diego Giuliani

Photo Credits “Primo Piano”